— A notable connection observed exclusively in expectant mothers who had previously smoked.

View pictures in App save up to 80% data.

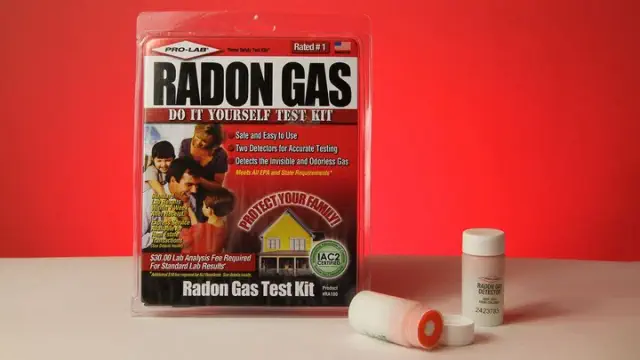

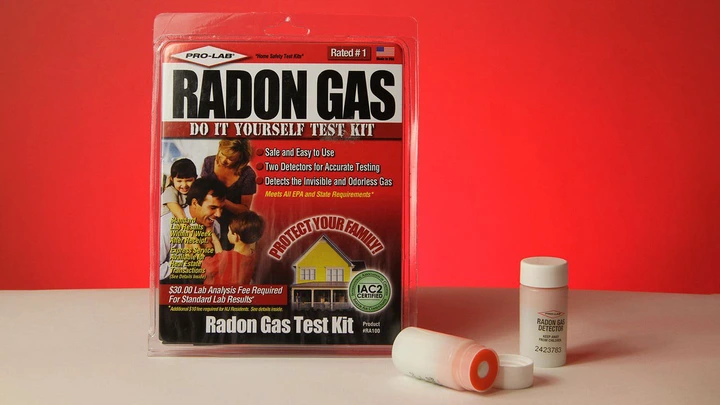

A population-based cohort study indicated that exposure to radon may be associated with a higher risk of developing gestational diabetes.

Among 9,107 mothers-to-be, those living in U.S. counties with the highest radon level (≥2 pCi/L) had a 37% greater chance of developing gestational diabetes compared with those living in counties with the lowest radon level (<1 pCi/L), Ka Kahe, MD, ScD, of Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York City, and colleagues found.

Even after adjustment for fine particulate matter air pollutants (PM2.5), which may share a similar biological pathway to radon, exposure to radon was still tied with gestational diabetes with borderline statistical significance (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.00-1.86).

The researchers explained in JAMA Network Open that radon and radon decay products emit alpha particles that can induce oxidative stress and promote inflammation, which both are implicated in chronic inflammatory disease like hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

"They also noted that exposure to radon could cause DNA damage and epigenetic alterations in placental cells, along with impairments in mitochondrial function. Collectively, these interconnected mechanisms might result in placental vascular issues by hindering blood circulation and nutrient transfer, leading to hypoxic environments that foster insulin resistance."

"Radon is possibly the most prevalent indoor carcinogen to which human beings are exposed," added an accompanying commentary by Alberto Ruano-Ravina, PhD, and Lucía Martín-Gisbert, MSc, both of the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain. "Some radon-prone areas are well characterized in the U.S. and Europe, but despite this, most of the population is unaware of the potential risks, including the interaction of radon with smoking."

Kahe's team utilized information from the Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: Monitoring Mothers-to-Be cohort. This study enrolled nulliparous pregnant individuals across eight clinical centers in the United States between October 2010 and September 2013. The average age of participants in this cohort was 27 years, with 41.6% reporting a history of tobacco use.

A clinical assessment identified gestational diabetes through a glucose tolerance test conducted as part of standard medical practice. Among the participants, 4.2% were diagnosed with gestational diabetes.

Radon exposure in counties was categorized into three groups according to the Environmental Protection Agency's assessments for short- and long-term indoor radon levels: below 1 pCi/L, from 1 to just under 2 pCi/L, and 2 pCi/L or higher. The average radon concentration at the county level was measured at 1.6 pCi/L. Individuals living in areas with the highest radon levels (≥2 pCi/L) tended to be predominantly white, had lower educational attainment, often not completing high school, and were less likely to be smokers compared to those in the lower exposure categories.

Notably, there was no correlation found between radon exposure and gestational diabetes in mothers who had never smoked (OR 1.31, 95% CI 0.84-2.05) or in those with a BMI of 25 or lower (OR 1.38, 95% CI 0.80-2.39).

On the other hand, the highest odds of gestational diabetes were among ever-smokers living in counties with the highest radon levels compared with never-smokers in low-radon counties (OR 2.09, 95% CI 1.41-3.11). Also, odds of gestational diabetes were elevated among those exposed to high radon and high PM2.5 levels compared with those exposed to low radon and low PM2.5 levels (OR 1.93, 95% CI 1.31-2.83).

Ruano-Ravina and Martín-Gisbert noted that the present research, similar to earlier investigations into radon, faced limitations by assessing indoor radon exposure at an ecological level through the use of counties, municipalities, or other geographic units. They emphasized that "these methods yield an aggregated radon concentration that is uniformly attributed as exposure for individuals residing in the relevant area."

They highlighted that radon exposure is recognized for its significant variability. "[E]ven in the same county, residential radon levels can vary greatly due to differing types of underlying bedrock," they noted, mentioning that even adjacent townhouses can show discrepancies in radon concentrations.

"They emphasized the necessity of conducting studies that assess individual radon exposure, as this is the most effective method to connect such exposure to specific diseases. 'Accurate radon measurements are both affordable and straightforward to obtain, with the sole requirement being that radon detectors need to be installed in homes for a minimum of three months, without the need for any personnel,' they stated."

The researchers concurred, noting that certain county-level radon measurements utilized in this research were collected in the 1990s and might not accurately reflect the radon levels at the time of the study.

However, the commentators emphasized that studies of this nature "serve as essential hypothesis generators," urging for ongoing research to further unravel the extensive health effects associated with radon exposure.

-

Kristen Monaco is a senior staff writer, focusing on endocrinology, psychiatry, and nephrology news. Based out of the New York City office, she’s worked at the company since 2015.

Original Source

JAMA Network Open

Source Reference: Zhang Y, et al "Radon exposure and gestational diabetes" JAMA Netw Open 2025; DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.54319.

Secondary Source

JAMA Network Open

Source Reference: Ruano-Ravina A, Martín-Gisbert L "Radon and disease -- It is time for more case-control studies" JAMA Netw Open 2025; DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.54327.